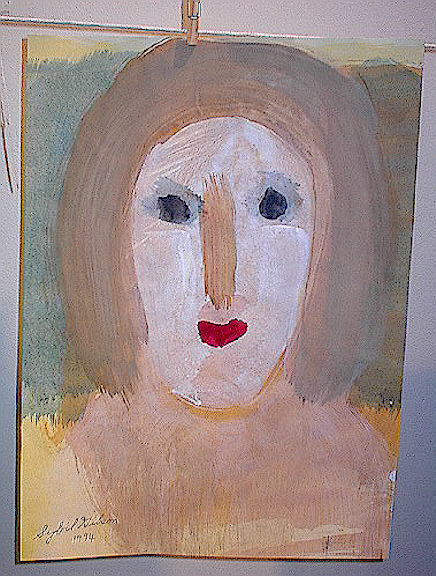

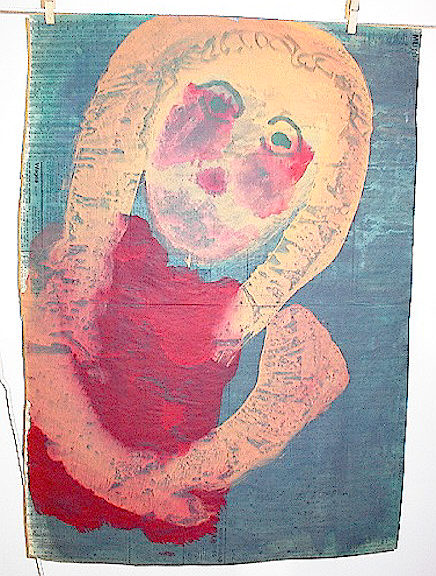

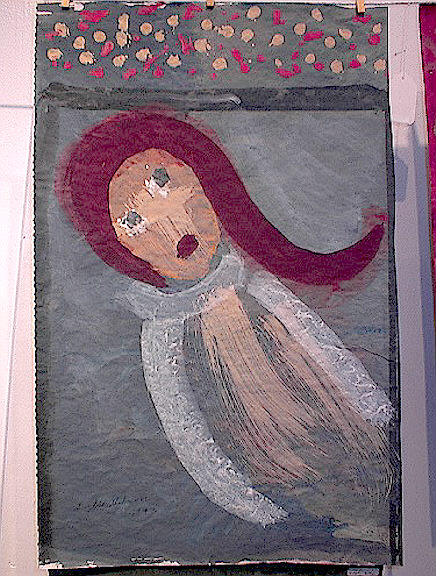

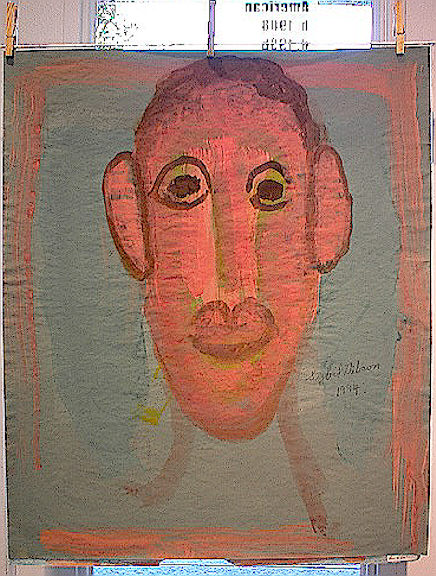

Spontaneous Combustion: Igniting the Creative Spark at Mid-Life, 2000

Everyone loves a good story, and few are as poignant as that of Sybil Gibson’s artistic awakening.

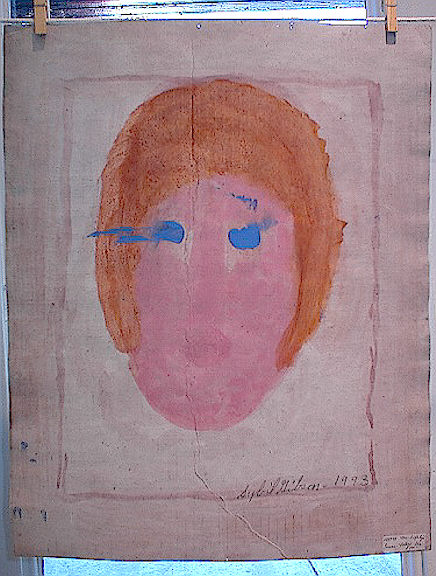

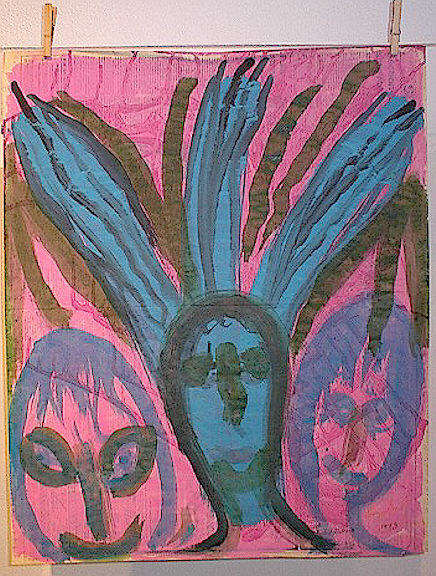

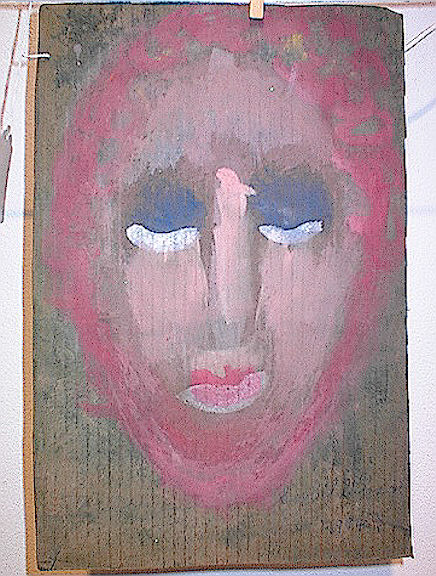

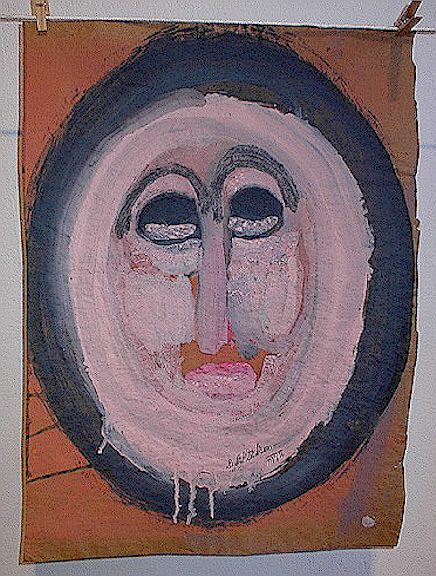

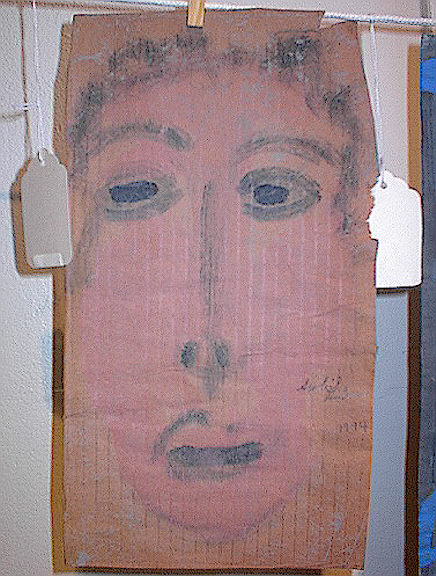

A schoolteacher who was widowed at 50, Gibson led an ordinary life until 1963, when she happened upon some gift wrap in a department store window that caught her attention. Seized by an urgent desire to paint, she went home determined to do just that. All she had on hand, recalled her daughter, Theresa Buchanan, were grocery bags and tempera paints left over from her classroom.

“She didn’t want to paint on folded-up bags, so she unglued the seams,” Mrs. Buchanan said. Gibson moistened them and went to work, completing 11 paintings that very day. Grocery bags and sheets of newspaper, always in abundant supply, served as her canvasses from that day on.

“She knew from the first painting that it was good,” her daughter said. “She was never unsure, not a moment.”

At first, others were less certain she was spending her time well.

“I’m a member of the family who said at first, ‘Oh, that’s nice…’,” Mrs. Buchanan admitted, “because that’s what Southern people do.”

Temporarily discouraged, Gibson put her paints away. But they didn’t stay there for long.

“Someone, I don’t know who, encouraged her,” Mrs. Buchanan said. “I don’t know what they said, but it was probably more than ‘That’s nice.’“

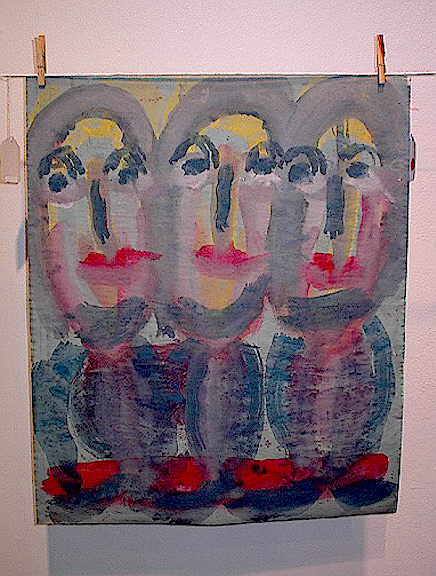

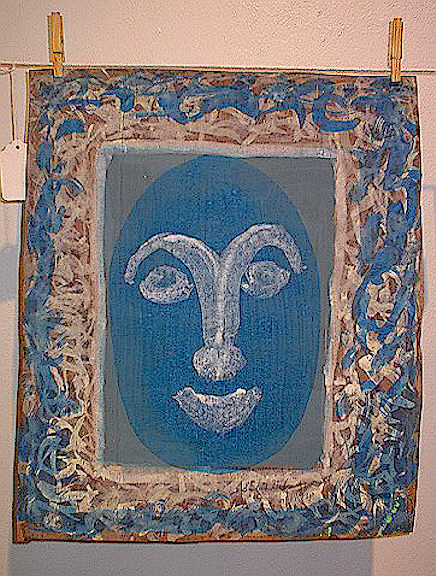

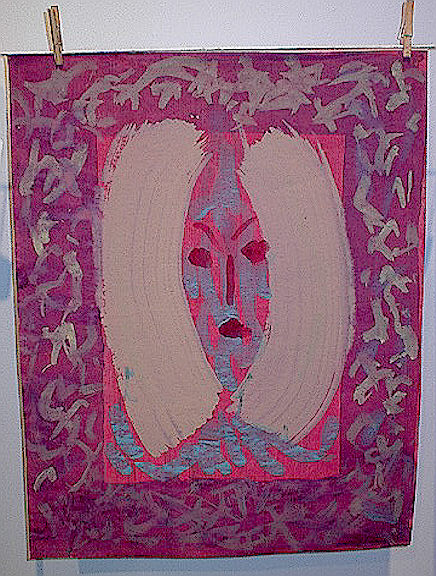

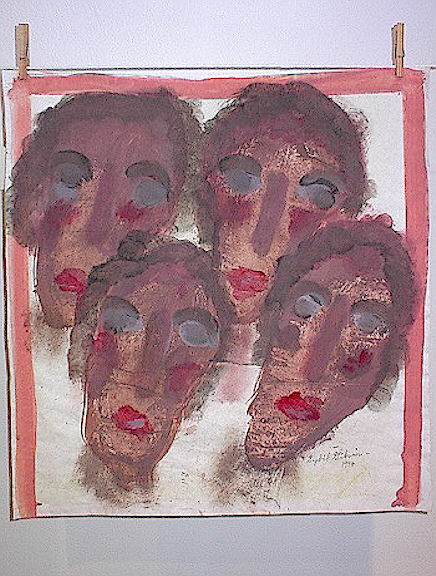

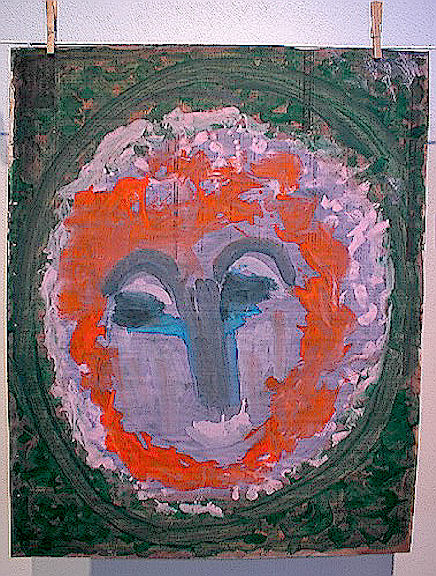

During those first years, recognition was slow in coming. Now Sybil Gibson is applauded in art circles around the country for a style that is distinctive in its fragility, tenderness and dream-like quality. Mrs. Buchanan attributes the latter largely to Gibson’s custom of painting on wet paper. “She loved to paint wet,” her daughter said. “If by chance the paper dried out before she was finished, she’d get it wet again. Having the paper wet worked with the flow, with the images not being so sharp. It gave her work an impressionistic character.”

Gibson painted avidly until failed cataract surgery in 1987 left her blind in one eye. Also affected by a cataract, the other eye worsened. Because of what had happened before, she refused to permit another surgery “as long as she could see a blur,” Mrs. Buchanan said.

Painting became impossible, and Gibson moved to a nursing home in Florida near her daughter and son-in-law, continuing to refuse treatment until the right surgeon could be found. There she met a young doctor “Sybil liked men,” Mrs. Buchanan said with a laugh, “and she especially liked young men” — who spoke with so much confidence and so positively about the surgery that she decided he would be the one.”

The doctor operated on what he later said was the worst cataract he’d ever confronted. “When the bandages came off that day,” said Mrs. Buchanan, “she could see. Six weeks later they gave her a pair of reading glasses to put on. She knew then that the danger was gone, and said, ‘Let’s stop at the paint store on the way back!’ “

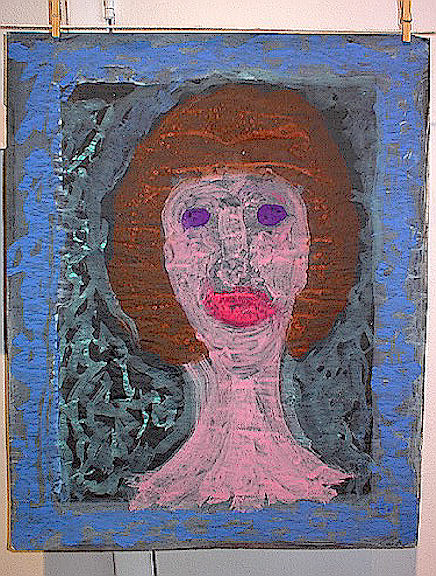

All the works in this show date from the period following her surgery until a massive heart attack brought Gibson’s painting career to an end in 1994. Her workplace in the nursing home consisted of the electric bed in her private room, which the Buchanans had obtained to replace the nursing home’s old crank bed. “We were showing her how the bed goes up and down,” Mrs. Buchanan recalled, “and there was this flat position it came to which raised it right up to table height. She said, ‘Let’s see you do that again.’ You see how alert her mind was? I would never have entertained the thought of using the bed for that.”

One of Sybil Gibson’s last paintings hangs here on the gallery’s northeast wall. It features a dark, swirling figure set against a brilliant yellow background. Headed by the inscription “Like nothing I done before is what I wanted to accomplish,” its style is radically different from Gibson’s other paintings. Might it possibly have pointed the way to a new path upon which Gibson was about to embark? If so this could have been a revealing voyage of discovery for an artist whose life’s work, as Robert Cargo put it in a recent essay, consists of “five or six paintings, with endless and magnificent variations.”