Just Injust, 2021

A Postcard

On August 7, 1930, in Marion, Indiana, two young Black men, Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, were murdered in a “spectacle lynching” witnessed by a mob of 5,000 residents of the city, including women and children. They had been jailed the night before, charged with robbing and murdering a white factory worker and raping his girlfriend. The crowd broke into the jail with sledgehammers, pulled them out, beat them and hanged them. Abram Smith’s arms were broken to prevent his efforts to free himself from the noose. Police officers in the crowd cooperated in the lynching. A local studio photographer, Lawrence Beitler, took a photograph of the hanged men’s bodies surrounded by the festive mob. Beitler published and sold thousands of copies of the photograph over the next ten days. It was one of hundreds of such photos sent and kept as souvenir postcards throughout the Cotton Belt in the first decades of the 20th Century. For many, lynching was photographic sport. A Song In 1937 Beitler’s photograph showed up in New York City and was seen by Abel Meeropol, a man who taught English at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. Meeropol, the Harvard-educated son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was also active in progressive social movements. He was horrified by the photo. It “haunted me for days,” he said. It inspired him to write a protest poem, “Bitter Fruit,” which compared the victims of lynching to the fruit of trees:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop:

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

Meeropol published his poem in the magazine New York Teacher in 1937 and later in the magazine New Masses, under his pseudonym Lewis Allan. With his wife, Anne, and the African American vocalist Laura Duncan, he set it to music and renamed it “Strange Fruit.” He and Duncan performed the song at a labor meeting in Madison Square Garden, where it came to the attention of singing star Billie Holiday. Holiday performed it at the Greenwich Village club Café Society in 1939 and recorded it on the Commodore label the same year. (Columbia, her contractual label, would not issue it.) The Commodore version eventually sold a million copies, in time becoming Holiday’s biggest-selling recording and the song most closely associated with her. In 1999 “Strange Fruit” was named “song of the century.” Over the more than 80 years since Holiday’s recording, it has been covered by countless other artists.

Another Postcard

In 1999 the fabric artist April Anue—whose legal name is April Thomas-Shipp—purchased a book, The Face of Our Past, a collection of images of Black women through American history, by Kathleen Thompson and Hilary Mac Austin, after it was featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show. The women are depicted largely in domestic, professional, social and other positive situations. But one is not: the book includes a photo of a lynching that took place in Okemah, Oklahoma, on May 25, 1911, taken by studio photographer G.H. Farnum and published as a postcard. The victims were a mother, Laura Nelson, and her 14-year-old son, Lawrence, hanged together from a bridge over the North Canadian River. “Until that moment, it never occurred to me that they lynched women also,” April writes. She has a son who at the time was five years old. “I thought: if an angry mob came after my boy, what would I do? Who do you turn to for help when the whole town is coming after your child? For a brief moment in time, I was there with that mother. I heard her cry, ‘Please, don’t take my boy! Please, don’t kill my son!’ I saw her cry, felt her pain. My heart began to ache. What crime had she committed, loving her son too much?”

A Quilt

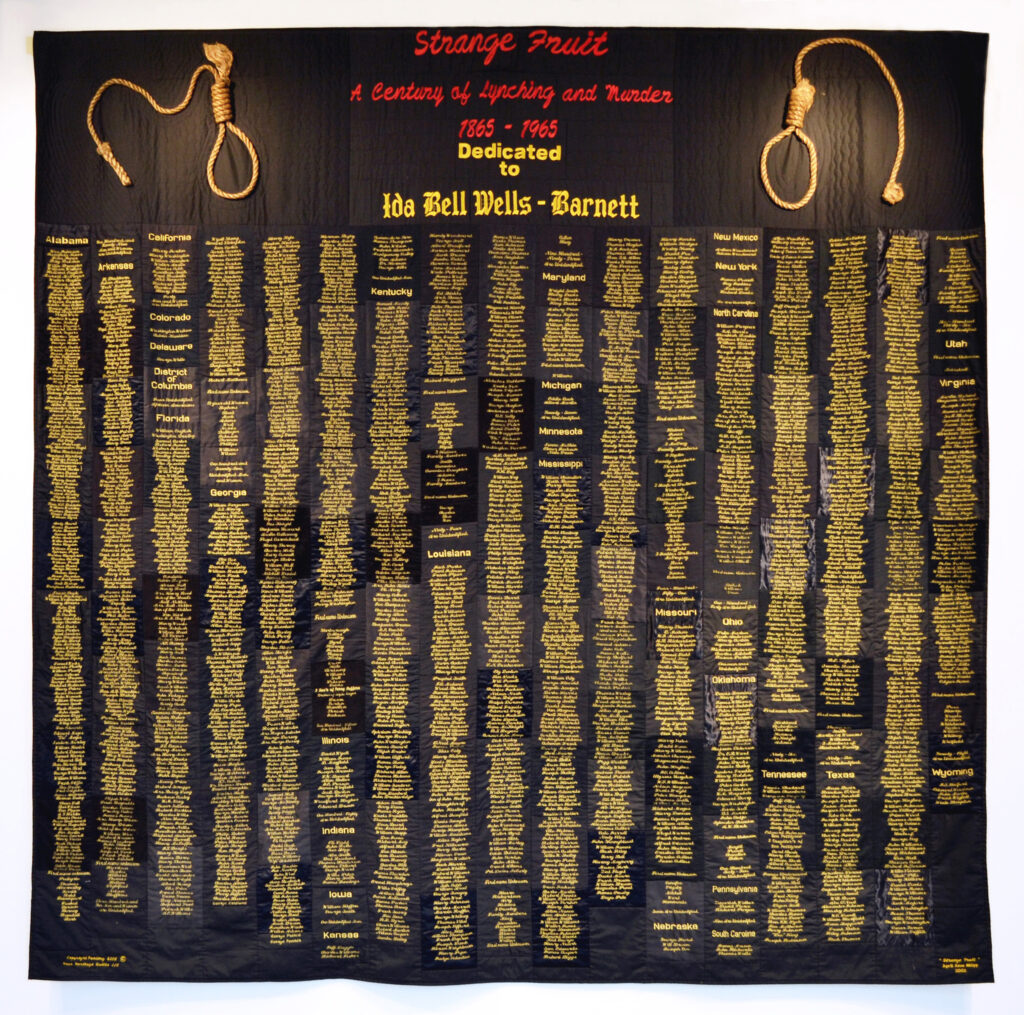

Thinking of the terror experienced by Laura and Lawrence Nelson and realizing that thousands of other African Americans had died in similar, unspeakable ways, April Anue began to pray. “Father God, someone needs to do something about this,” she pleaded, “These people need to be known—if not their stories, at least their names. They were people, my people!” Today she says she believed the Spirit of the Lord answered her: “Find their names and make a quilt.” “I can’t,” was April’s immediate reply to the Lord. She poured out all the arguments she could think of against taking on such a task: the quilt would be too big; the work would be too hard; she hadn’t the experience or qualifications; the Lord would do better to pick someone else. “Needless to say, He won, and I began to make the quilt.” The project took three years of painstaking research and arduous work. April discovered that fastidious records of the killings had been kept by the groups that carried them out, as well as by local authorities, and that other lists had been compiled in more recent times by journalists and scholars, often based on the mass of lynching postcards and memorabilia that survive in historical archives. Between 1865 and 1965 (when lynchings fell off steeply due to potent federal civil rights legislation), nearly 5,000 Black Americans were executed without justice at the hands of vigilantes and white supremacists. Theirs were the names she committed to her quilt, by the states in which they died, in gold embroidery on black fabric: “My five thousand souls.” She finished and signed the work in 2002. She called it “Strange Fruit,” after the iconic song. April dedicated her quilt to the American investigative journalist, educator, and early civil rights leader Ida Bell Wells-Barnett (Ida B. Wells), whose pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases, published in the 1890s, exposed lynching as terrorism by whites in the South who saw their power threatened by African Americans as economic and political competitors.

“Strange Fruit,” by April Anue, measures 10 feet long by 10 feet 6 inches wide and weighs 12 pounds. While its columns of names of known persons in themselves can overwhelm the viewer, its exclamation mark is the substantial numbers, also embroidered by state, of those known perhaps only to God.

“In making this Quilt, I learned that it did not matter who you were: Detective Albert Parker (lynched 1868) or Reverend L. C. Baldwin (murdered 1956). It did not matter how old you were: Virgil Ware, age 13 (murdered 1963) or the 3 murdered children of Thomas Harris. It could happen to anyone, anywhere, anytime. I made the Quilt in memory of my people, people I have never met, people whose names are woven not only into the fabric of my work but also into the fabric of my heart.”

Notes

There was a third youth arrested with Shipp and Smith and then seized by the mob in the 1930 Indiana lynching incident. He was James Cameron (1914-2006), 16 years old at the time. With his two older friends he was taken from the jail cell and beaten; but before he could be hanged two witnesses vouched for his innocence in the murder and he was returned to stand trial. Cameron was convicted as an accessory and served four years in prison. After his parole he moved to Detroit, where he worked at the Stroh Brewery and studied engineering at Wayne State University. At the same time, he studied lynchings, race, and civil rights. Returning to Indiana, he served as State Director of Civil Liberties from 1942 to 1950, facing violence and death threats because of his work. Cameron finally moved with his family to his home state of Wisconsin, where he continued to organize, lecture, and publish on the African American experience. In 1988 he founded America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee. In 1991, he was pardoned by the State of Indiana.

In May 1908, in an effort to stop the use of lynching photos as postcards, the federal government enacted postal regulations banning “obscene matter” “…of a character tending to incite arson, murder or assassination” from being sent through the mail. The cards continued to sell, although not openly, and were sent instead in envelopes. Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), having been emancipated from slavery during the American Civil War, owned and wrote for the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper in Tennessee, covering incidents of racial segregation and inequality. A white mob destroyed her office and presses, but not before her investigative reporting made it into newspapers nationally. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 2020 she was posthumously honored with a Pulitzer Prize special citation “[f]or her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.

April Anue used a Husqvarna Viking Designer 1 machine and Sulky Gold no. 7007 thread to embroider the names. The fabrics are various shades of black to symbolize the color of her people. The textures represent the various positions in life of those who were murdered, i.e. silk, cotton, and denim.

By Michael Madigan

March 2021